Image by Katie Rodriguez on Unsplash

Media has power. Throughout history, from newspapers to radio, then television and finally the Internet and social media, media has given a voice to ideas and the people behind them. Communities of climate change activists and victims of sexual harassment have never been as strong as they are now thanks to the arrival of figures such as Greta Thunberg and Tarana Burke. Once being just one in many, these visionaries found a way to use media to reach thousands of people around the world, who then got empowered by movements such as FridaysForFuture and MeToo and the shared ideas they stand for. How does this happen? What does empowerment really mean and what can communities do with media when it comes to sustainable development?

What is community empowerment?

First, let’s break down this term into two parts. ‘Community’, as defined in the Cambridge dictionary, means either people living in one particular area or people who are considered a unit because of their common interests, social group or nationality. These communities could be local, national or international, with specific or broad interests. For example, a community could be a group of dog owners in the local neighbourhood that meet in the same parks and share similar interests towards caring for dogs or a community could be a forum of international working women in the city, where women share their knowledge and experience of integration with the local workforce.

‘Empowerment’ happens when people gain control over the factors and decisions that shape their lives (WHO). It is the process by which people build the capacity to gain access, partners, networks and a voice in order to gain control. So, community empowerment happens when communities increase control over their lives; however, they achieve this not by being enabled by others, but by finding the power within themselves (Labonte, Laverack, 2008). The role of media as an external agent is to catalyse, facilitate or ‘accompany’ the community in acquiring this power.

Community empowerment, therefore, is more than the involvement, participation or engagement of communities. It means community ownership and action explicitly aimed at social and political change (Baum, 2008).

How do communities become strong?

Communication and media play a vital role in ensuring community empowerment and building partnerships among different sectors in order to find solutions. Discussion and debate enabled inside the community by means of media increase knowledge, awareness and the level of critical thinking (WHO). Critical thinking is needed by communities to understand how different forces influence their lives and to help them make their own decisions. However, due to the unequal distribution of technology, several communities worldwide are experiencing diverse stages of empowerment. For example, it is clear that the community just recently introduced to the radio is less technologically advanced than the community which recently experienced the Internet. Community media or community broadcasters therefore play a crucial role in informing and engaging the community. Read on to find out more about them in the next paragraph.

Community media/broadcasters

According to UNESCO, community broadcasters are privately owned radio and television stations, as opposed to the public media. Most importantly, they are independent from the government but also from political control more generally. Unlike commercial broadcasters, they generate revenue not for making profit, but to support the broadcasting service.

Community broadcasting serves the community. It is produced in a language or languages commonly used, spoken or understood by the community and covers issues of immediate and special relevance to the community, whether of a social, cultural, political, economic or other nature (UNESCO).

In regard to social inclusion, a study conducted on community radios across Switzerland, Germany and Austria in 2018 concluded that “unlike most ‘professional’ media, community media have a relevant history of capacity building and inclusion of refugees, migrants, and second & third generation citizens – in both production and management. Within the context of the ‘refugee crisis’, community media are a crucial point of contact, mediation and training, enabling the rights of access to information and freedom of expression as well as fulfilling the need to speak in one’s own voice” (Bellardi, 2018).

Technology advancement drives down the costs of media production (Chalaby, 2007). Access to media becomes cheaper, too, and so we see local community forums, podcasts, radio and TV channels mushrooming in developing countries, driving local societies towards sustainable development. A few examples are listed below.

Arab Spring

It is not biased to say that contemporary discourse on the use of new media, especially social, has risen dramatically since the Arab Spring in 2011 (Vaiciulyte, 2012). “In the Middle East, satellite ventures have introduced innovative TV formats and driven vast changes in Arab television. Channels such as Al Arabiya have raised the standards of broadcasting journalism and the independent voice of Al Jazeera has unsettled governments” (Chalaby, 2007). Discussions broke on whether social media (Facebook, Twitter, etc.) is responsible for the scope of the Arab revolution (Hothi, 2012). Various critics are on the case, but they cannot deny the fact that social media has acted as a communication tool for political mobilisation.

Opposition in Russia

By 2020, the political opposition in Russia has gained an unprecedented social following through the social channels of Meduza and Novaya Gazeta (independent news agencies) and TV Rain (an independent TV station). The community formed around these channels actively engages in strategic actions such as Smart Voting, developed and promoted by Alexey Navalnyi’s Fund for Fighting Corruption, which has led to structural changes in regional governments.

Swedish climate change activism

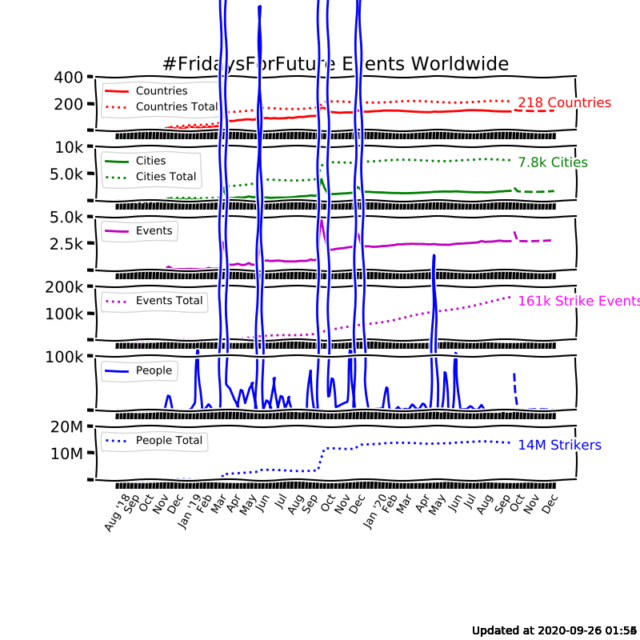

Fridays For Future is a global strike movement that started in August 2018 in the three weeks leading up to the Swedish election, when 15-year-old Greta Thunberg began a school strike for climate, spending days outside Swedish Parliament. Initially, she was alone, but then joined by others; her call to action sparked an international awakening, with students and activists uniting around the globe to protest outside their local parliaments and city halls (Fridays For Future). Below, you can view statistics on FFF events throughout the first two years of its existence.

How can anyone achieve such success over and over again? The answer is that this movement is independent and people-led (anyone can register a strike) and that the community is very self-organised, meaning that inside the community you can find everything and everyone you need to coordinate and promote the strike.

“We found that social media really helped activists to network and communicate better with one another. It meant that information flowed much quicker than it did before, with activists no longer dependent on meetings or chance encounters on the street to share news,” wrote Mandeep Hothi for The Guardian on the study of the ability of social media to empower a local community in the UK in 2012. “It makes community activity much more visible. Simply being able to observe means a wider group of people are informed, even if they choose not to take their involvement further” (The Guardian).

Sustainable Development

Ever since the concept of sustainable development was described by the 1987 Bruntland Commission Report as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”, the most remarkable instrument for its promotion became the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals. They are the blueprint for achieving a better and more sustainable future for all and they speak to the commitments of both the government and private sector; multi-stakeholder effort is crucial to induce action towards the goals. They address the global challenges we face, including poverty, inequality, climate change, environmental degradation, peace and justice (un.org). As a strategy to achieve the SDGs, the World in 2050 (TWI2050) presented six key transformations that include digital revolution, smart cities, food, biosphere & water, decarbonisation & energy, consumption & production and human capacity & demography.

SDG promotion: the Samsung case

Myriad social initiatives have been promoting the SDGs, but one remarkable example to be highlighted here is how Samsung, a private company, in partnership with the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), gave its customers the opportunity to promote and raise funds for the SDGs through installing the free Samsung Global Goals app on their phones. The funds come from the ads shown to the user when using the app. Once the user collects the funds from watching the ads, they can decide which of the 17 SDGs those funds shall be donated to. Additionally, the app raises awareness of the SDGs through placing colourful wallpapers on the user’s phone screen.

Viral content influencing private sector through media: the Lego case

In 2014, GreenPeace ran a campaign against Shell’s ambitions to drill for oil in the Arctic. They released YouTube short film ‘Everything is NOT awesome’ depicting an oil-stricken Arctic built from around 120 kg of LEGO bricks as “the latest salvo in a campaign by the green group to pressure the world’s largest toymaker to drop a partnership that distributes its toys at Shell petrol stations” (The Guardian). This video went viral and hit 1 million views a day after it was launched. Three months later, the goal was achieved; LEGO announced that it would not renew its contract with Shell (Greenpeace). It is worth noting that YouTube, as a media contractor, had its own responsibility to stakeholders, including Warner Bros, the studio behind The Lego Movie, who filed a copyright complaint to YouTube. Three days after the release of the viral video, which by then had reached 3 million views, YouTube removed it. Greenpeace then uploaded the video to Vimeo, where it remains available today.

Petitions as an instrument for community action

A petition is a document signed by a large number of people demanding or requesting a certain action from the government or another authority (Cambridge dictionary). The rise of online social networking in the late 2000s, however, resulted in both an increase in the integration of Internet petitions in social networks and an increase in the visibility of such petitions; Facebook, Change.org, Care2, Avaaz.org, SumOfUs, GoPetition and other sites serve as examples of the integration of Internet petitions as a form of social media and user-generated content.

In some cases, petition sites have managed to reach agreements with state institutions on the implementation mechanism of widely supported initiatives. Thus, the platform ManaBalss.lv in Latvia has the authority to hand over to parliament any legally correct initiative that has been signed by more than 10,000 authenticated supporters.

Most successful Internet petitions

On 23 March 2019, the record for the greatest number of verified signatures on an official government petition was broken in the UK. The petition moved against the UK government’s decision to leave the European Union following the Brexit referendum and had collected over 6 million signatures (The Guardian). The international record for most successful online petition is currently held by the change.org petition for the death of George Floyd, which was started by a 15-year-old girl from Portland, USA (peoplesworld.org). In just 4 months from its publication in June, it has gained over 19.6 million signatures and counting.