Image is illustrative. Jon Tyson (Unsplash)

The link between online communities and radicalisation

On 15 March 2019, the Christchurch shootings took place in New Zealand, with the assailant streaming his attacks live. Facebook removed the video from its platform and blocked over 1.5 m copies of it, mostly before the uploads finished (Hern, 2019). The live stream was accompanied by a manifesto full of internet culture references and racist ideology. Both contents spread like wildfire, far beyond Facebook and YouTube. This shifted the focus of the media to make a link between online communities and radicalisation. While he was not the first such shooter, he most clearly showed where he had been radicalised, on anonymous message boards that share edgy humour interlaced with extremist positions.

What is extremism?

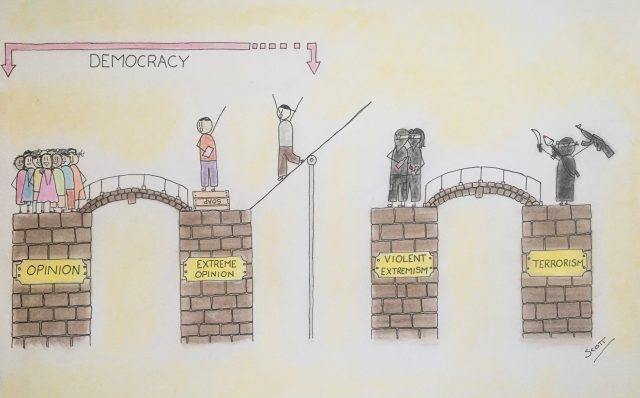

The Anti-Defamation League defines extremism as “A concept used to describe religious, social or political belief systems that exist substantially outside of belief systems more broadly accepted in society (i.e., “mainstream” beliefs). Extreme ideologies often seek radical changes in the nature of government, religion or society. […]” (Anti-Defamation League , 2019).

A subset of extremism is so-called violent extremism. As the UN notes in their “Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism”: “Violent extremism is a diverse phenomenon, without clear definition. It is neither new nor exclusive to any region, nationality or system of belief.” (United Nations General Assembly, 2015). While not clearly defined, it is understood that violent extremism is perpetrated with destructive means by people with strong ideologies against commonly accepted values in society. Radicalisation is the process of developing extremist ideologies or beliefs, which can lead to violent extremism. However, it seems that violence and ideology do not have to mix (Borum, 2012).

The internet is a massive social experiment, with many niches and sub-communities for all kinds of interests. It is of little surprise that extremist groups also find fora to meet up, exchange their opinions and create communities. A report by the Data & Society Research Institute has outlined the connections within the “Alternative Influence Network” on YouTube (Lewis, 2018). The network consists of political influencers, who strategically seek to shift the dialogue to accommodate more extremist political positions. Their strategy uses YouTube’s suggestion algorithm and manipulates it through cross-promotion with moderate influencers and brand marketing strategies, and it creates a pathway from moderate to extreme content on the platform. These pathways make it easier to become exposed to more extremist content, while looking for an adjacent topic, in particular if the young people pick up the narrative and terminology used in the videos. These videos are also a launch pad deeper into extremist communities outside of the platform. These communities often come together on anonymous message boards such as 4chan, its successor 8chan or privately hosted websites or encrypted messenger channels. Within these communities, radicalisation can fester and push people towards more extreme ideas.

Filter Bubble and the Echo Chamber Effect

A filter bubble can be created through the exchanges in these communities, as described in Eli Pariser’s book The Filter Bubble (Pariser, 2011). Such bubbles are limitations generated by content sorting algorithms of internet service platforms like the Google search engine, YouTube or the Facebook timeline. According to Pariser, they restrict the content we are exposed to, in order to show content that is agreeable to the user. This is accompanied by the Echo Chamber Effect (DiFonzo, 2011), which describes the natural human instinct to seek out communities that reaffirm one’s beliefs. In these echo chambers, opinions and attitudes are reflected back and supported, which supposedly leads to the participant siding ever stronger with the shared opinions and values of the given community. However, a 2016 Facebook study (Bakshy, Messing, & Amamic, 2015) has shown that the effects are smaller than initially suspected. The scientists pointed out that the influence of users on what can be seen remains more substantial than the algorithms. It remains unclear whether the effect would be more pronounced with younger participants.

The Christchurch shooter was not the first to be radicalised through such channels, nor has he been the last. On 9 October 2019, a similar attack took place in Halle, Germany. The shooter copied many of the elements of the Christchurch attacks, including the manifesto. His way of radicalisation seems to match the same pattern as that of the Christchurch shooter.

Preventing youth radicalisation

Currently, monitoring of these communities is desperately needed. At the same time, these communities are self-regulated and fight against any external influence. Due to the anonymised profiles on these platforms, it is difficult to create credible profiles of the participants. The safest approach is to reach young people before they become radicalised and out of reach in these communities. In the process of radicalisation, the communities tend to shut off contacts to interventions and create resentment against civil society and mainstream actors. At that point, only so-called EXIT initiatives offer solutions for removing people in the extremist communities. They offer information and contact points inside the communities and reach out directly to group members in doubt, in order to offer them exit strategies on how to leave the community without losing all social contacts or risking harm.