Critical Thinking

Year of production: 2020

Image is illustrative, Pixabay

At first, the concept of critical thinking might seem quite straight-forward and clear. From our early years, we learn that trusting strangers, even if they seem friendly and nice, might be dangerous. With time, though, we might find ourselves completely fooled by a misleading ad, a piece of breaking news or a passionate speech by a respectably looking politician. When did we lose our grip?

“We live in a world of almost total mediation,” states renowned British writer and media education researcher David Buckingham. “New challenges have emerged, for example in relation to ‘fake news’, online abuse and threats to privacy; while older concerns – for example about propaganda, pornography and media ‘addiction’ – have taken on new forms. The global media environment is now dominated by a very small number of near monopoly providers, like Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon, who control the most widely used media platforms and services, and yet whose power is much less overt and visible than the power of older ‘mass media’ corporations. We all need to think critically about how media work, how they represent the world and how they are produced and used.” (Buckingham, 2018).

A media educator or a youth worker can play a vital role in helping a young person learn to think for themselves and make their own judgement. How do we make this happen and what are the key themes to pay closer attention to when discussing critical thinking? Let’s start with the basics.

What is critical thinking?

Critical thinking is clear, reasonable, reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do (Lumen Learning). According to Facione (1990), we use several skills when we think critically:

- we listen (focus on what is being said – and not said)

- we analyse (consider in greater detail, separating the main components of the message)

- we evaluate (assess various claims and arguments for validity)

- we explain (consider evidence and claims together)

- we self-regulate (consider our pre-existing thoughts on the subject and any biases we may have)

We need critical thinking skills to help our brain’s natural tendency to simplify things. Cognitive Distortions: What They Are and Why They Happen by Very Verified presents the most common biases along with a few examples, which are easy to relate to.

Key concepts crucial to understanding media through critical thinking

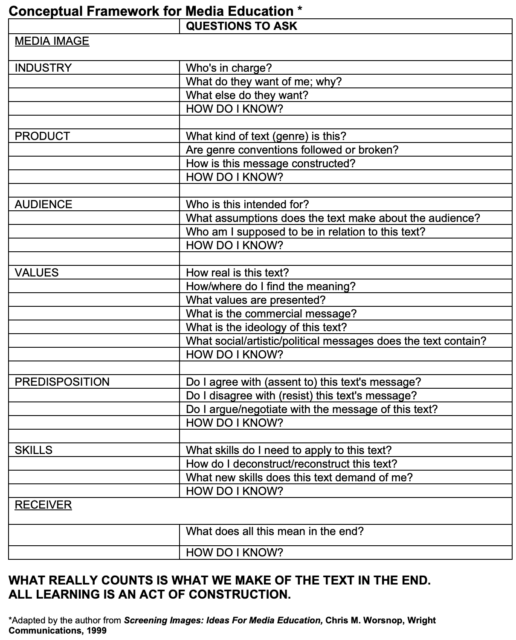

These Teacher Materials by Chris M. Worsnop, produced by NW Center for Excellence in Media Literacy (College of Education, University of Washington), lay out the five key concepts crucial to understanding media through critical thinking. These concepts may not be found all at once in a single media text, but rather they often overlap.

All media are carefully wrapped packages

As carefully wrapped packages, the messages are ‘wrapped’ with enormous effort and expense, even though they appear quite natural to the audience. Media texts are the product of careful manipulation of constructive elements, both on an obvious and a subtle level. On an obvious level, constructions such as drawings, colours and headlines may be used. But on a subtle level, constructions such as appeals (generalisation appeal or appeal to emotion) may be used. Young people need to develop the skills of looking beneath the surface of media messages to see how they are constructed.

Media construct versions of reality

Audiences tend to accept media texts as natural versions of events and ideas, when, in fact, they are only representations of events and ideas. The reality we see in media texts is a constructed reality, built for us by the people who made the media text. Young people need to develop skills of interpreting texts so that they can tell the difference between reality and textual versions of reality.

Media are interpreted through individual lenses

Audiences interact with media texts in their own individual ways. Some audiences accept some messages totally at face value. Other audiences may reject the same text, disagree with its message or find it objectionable. Yet other audiences, not certain if they have embraced or rejected the text, will try to come to terms with it by negotiating. Audiences who negotiate with a text might ask questions, seek out other people’s opinions or try several interpretations or reactions the same way we try on new clothes—to see how they suit us. Young people need to be open to multiple interpretations of texts and aware that a reaction to a text is a product of both the text itself and all that the audience brings to the text in terms of their accumulated life experience.

Media are about money

- Modern media are expensive to produce. Producers need to make back their investment by marketing their product to audiences.

- One of the main purposes of the media is to promote consumerism. While we enjoy many of the products of media, such as magazines, we need to be aware that some media texts are created to deliver an audience to advertisers rather than to deliver texts to audiences. Others may use consumerism as a secondary motive.

- With increasing regularity, four or five massive communications conglomerates dominate media production facilities such as newspaper/book/magazine publishers and TV/film production and distribution companies. Young people need to be aware of the implications of media’s commercial agenda and how ‘convergence’ affects media and their contents.

Media promote agenda

The very fact that some people object to some media texts is proof that those texts contain value messages. Most media texts are targeted to an audience that can be identified by its values or ideology (belief system). Detecting the ideological and values agenda of media texts is an important skill in media analysis.

As a guide to action, Teacher Materials (C.M. Worsnop, NW Center for Excellence in Media Literacy) presents a list of questions a young person should ask when thinking critically about the piece of content at hand.

What are different approaches to critical media education and how have evolved over time?

In his article entitled Going critical, Buckingham (2018) gives a retrospective of his teaching experience. He says it started with the ‘demystification of media’ in the 1970s, when critical analysis aimed to see through media ideologies and realise the truth behind the message. Knowledge which was hidden from view (such as media ownership and control) was coupled with alternative representations that challenged sexism and racism within media.

Content creation came in the next decade as a more creative alternative that offered a space in which students could reflect on their own engagements with media. Focus was moving to the cultural and aesthetic dimensions of media and, in the 90s, resulted in the realisation of how our emotions affect our media perception and our behaviour and also how much knowledge students already possessed of the media themselves.

As personal computers and smartphones became more and more available in the 2000s and social media entered the media landscape, people discovered new opportunities for participation online. “In terms of media education, they generated new objects and issues for study; but they also created new possibilities for the classroom, in terms of how teachers and students might access, create and share media.” (Buckingham, 2018.)

Training critical thinking through discussing images

What’s Going On in This Picture? (WGOITP? activity) is a feature of The New York Times, which invites teachers and students to use a bank of 40 intriguing images, all stripped of their captions or context, to practice visual thinking and close reading skills by holding a “What’s Going On in This Picture?” discussion or writing activity. There is also a workshop on how to use the WGOITP? activity, a lesson plan and a new Picture Prompt feature to get students writing, thinking, speaking and listening.

Recommendations for teaching critical thinking in media

Buckingham gives four recommendations for media educators to stay on the right course:

- We should be asking questions about the various ‘languages’ of these media – the forms of grammar or rhetoric they employ.

- We should be looking at representation – at how different social groups are represented and how they represent themselves in these online spaces.

- We should be looking at the changing institutional structures and economic strategies of these new media companies.

- We should be looking critically at how people engage with these media – albeit perhaps more as ‘users’ than ‘audiences’.

To educators the true purpose of critical thinking lies in debate through dialogue, rather than in making the students agree with a predefined position on a topic. Make use of the key concepts to ask difficult questions to the media and also to yourself. To make the learning experience meaningful, use a variety of approaches, such as reflection on media content and creation of new artifacts, and don’t forget to make space for all opinions and thoughts – young people may surprise you with what they know and the way they perceive the same content you see. Be inspired to share views, look for evidence, make claims and show flexibility in thinking. We adults may also be wrong at times.