The Croatian Debate Society (Hrvatsko debatno društvo) has been a trusted Erasmus+ and European Solidarity Corps beneficiary for years. With their project Point (Not) Taken, they have reiterated the importance of their work, as it focuses on fighting discrimination against minority groups by developing media literacy and critical thinking skills in one of the most impressionable segments of society – high school students. The research they conducted showed a worryingly low level of media literacy among the students and should be understood as an urgent call to reform the educational system. Having had the chance to review the works of students who participated in the journalistic and media workshops, the Croatian Debate Society demonstrated how much progress can be achieved when we begin educating and guiding our youth early on. This success story has inspired us, as a national agency, to continue strengthening our support for beneficiaries in addressing these important topics through their projects.

Point (Not) Taken: media literacy skills for high school students in Croatia

To address the increasing rate of discrimination observed among young people in Croatia, the ‘Point (Not) Taken’ project introduces high school students to essential media literacy skills. Through interactive workshops, focus groups, and practical journalism tasks, students learn to identify fake news, explore the principles of ethical journalism, and reflect on media portrayals of social groups.

We saw a drastic increase in discrimination towards certain social groups among high school students and young people all around Croatia. This can be largely attributed to how the local media portrays these groups. For example, in Croatia, the ethics of journalists aren’t necessarily always in line with moral ethics when reporting about Romani people. When such stories are written only from a certain perspective, there is a fertile ground for growing discrimination.

We asked ‘Point (Not) Taken’ coordinator Alma Beriša to share the story of the project – from its inception to implementation and future plans.

How did the project ‘Point (Not) Taken’ begin?

Alma Džafić, my colleague from the Croatian Debate Society, came up with the idea that we should go directly to high schools and actually teach students about media literacy, fake news, discrimination, and what proper journalism should be like. Three months went into forming a team, planning the activities, and choosing high schools to participate. Eventually, we had five different high schools on board, both vocational schools and gymnasiums. At each school, we first held a 45-minute focus group, then a 45-minute workshop. Then, we gave students homework and mentored them to create an actual piece of journalistic content themselves.

Who was on your team, and how was it formed?

We had people from different backgrounds on our team, including journalism, social psychology, and political science. We all met through the Croatian Debate Society. Alma Džafić led the planning, and coordination of the project. My role was to help organise the focus groups and workshops, and later lead some of them.

What challenges did you face working with high school students?

At the time of the project, five out of six people on our team were college and university students. So the biggest challenge for us was to manage our calendars and hold the meetings.

Another challenge for the team was getting to know each other. Even though we knew of each other from the Debate Society, we didn’t know much about each other personally. Initially, it was a bit uptight, but later on, it was amazing – the division of work was excellent, and if someone had little time because of their exams, other team members would step in without any problem.

My biggest personal challenge was my age. I was 20 years old at the time of the project, just four years older than the youngest students. I had to establish my authority with them, but at the same time, I didn’t want to distance myself from them too much either.

The students also had to learn to work together, since, even though they were from the same schools, they came from different classes and most hadn’t communicated with each other before. So, they basically faced a similar challenge as our own team. We used a lot of icebreakers and energisers, and in the end, we created a really relaxed atmosphere in the groups.

How did you conduct the focus groups among students?

We had five focus groups in five different high schools, usually with nine to 12 students in a group, for a total of 40 to 50 students. The questions were the same in each group, and we later wrote a research paper using the gathered data. We asked questions like ‘What major newspaper do you know?’ and ‘Which media do you use to find information?’ The answers were almost always TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube. The students didn’t know about major Croatian newspapers or even global news networks like CNN. They didn’t read about what was happening in the world beyond scandals discussed on social media platforms.

That is indeed a dangerous ground for misinformation to spread. How did you tackle that in the workshops?

Workshops all had the same topic and the same goal: to teach students about fake news and how different social groups are represented in the media. For example, I started with four different articles, one of which was fake news, and I asked students to identify which one was fake. The task turned out to be surprisingly challenging, so then we went through the steps to identify fake news and discussed how fake news can affect people and their views.

You’ve mentioned giving students homework to write an actual news piece. How was that organised?

After we gave them the task, we held some online meetings and real-life meetings in schools to help them with their work. All the other communication went through their teachers, as we didn’t want to actually get the students’ private information, to stay GDPR compliant.

Surprisingly, the students did not require a lot of guidance, and when they asked for help, it was usually very thoughtful – they wanted to attract more readers but, at the same time, stay within the boundaries of journalism ethics and avoid using inappropriate methods.

How did you evaluate the results of the homework?

In total, the students produced four articles and one video presentation. Our team reviewed all their work and provided feedback. The results were so good, it didn’t actually leave us with much space to criticise them for anything wrong or inappropriate.

At the end of the project, we held a common meeting for all groups to present their work. There were even students who didn’t participate in the project. The feedback from those students was excellent – they were proud of their peers for doing such a good job.

This sounds great indeed! What were your next steps? I believe you mentioned a research paper?

We wrote a research paper based on the data gathered during the project. The paper ends with conclusions on what decision-makers should do to teach people, especially high school students, media literacy. Our first suggestion – and the students actually suggested it themselves – is to have the subject of media literacy in high schools as a mandatory class. Out of the five schools we worked with, only two had media literacy, which was non-mandatory, even though the students showed great promise and interest in the subject.

Any future plans for this project?

The plan is to start a new project on the same topic but with more students, produce an even bigger research paper, and create a brochure that we can present to decision-makers and local politicians, to actually have them discuss making media literacy a mandatory subject.

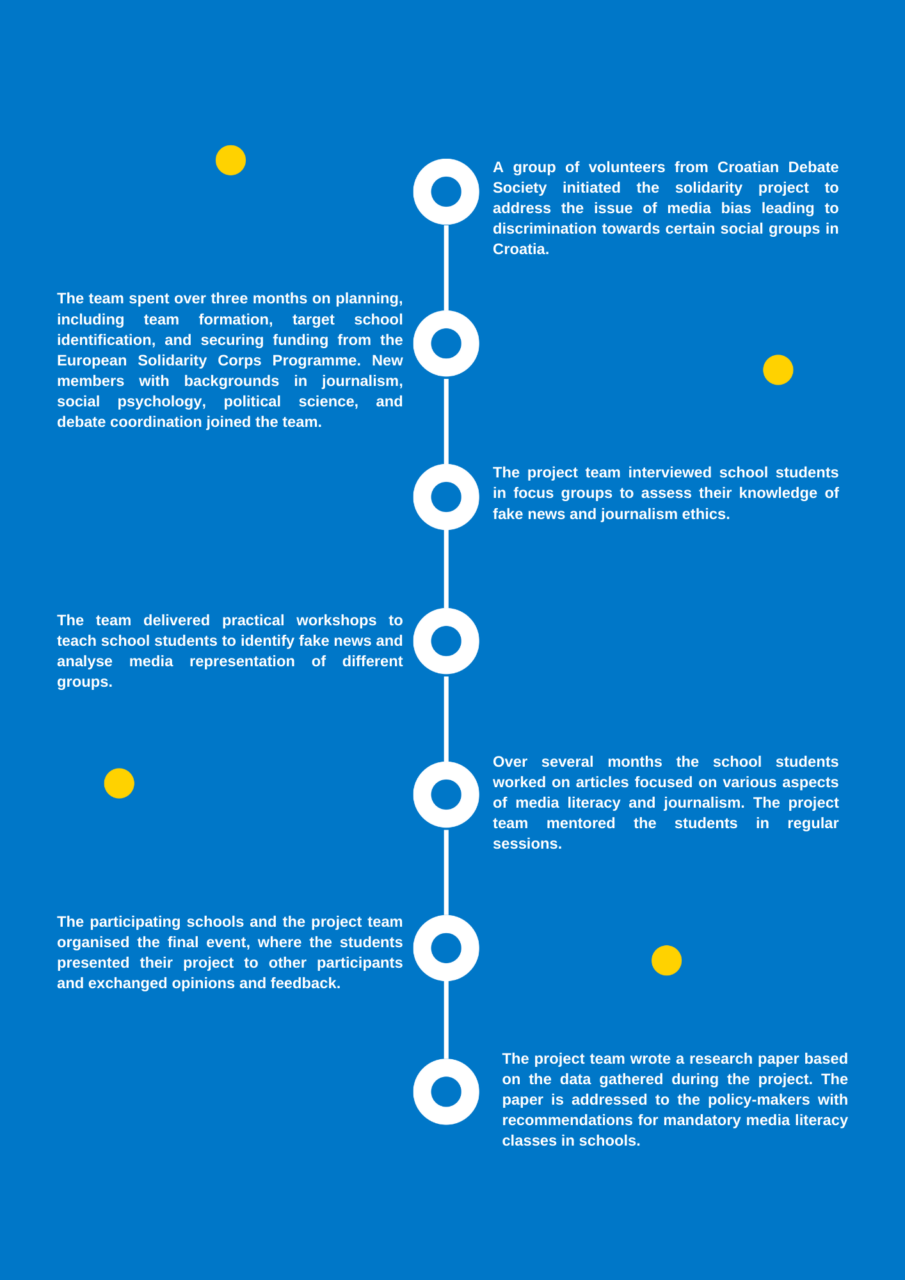

Project Roadmap

Project outcomes

The ‘Point (Not) Taken’ project engaged 50 Croatian high school students in workshops on fake news detection and ethical journalism. The findings were compiled into a research paper recommending educational reforms in media literacy.

Research Paper

Using qualitative analysis of the data gathered during the project, the research paper ‘Pametnom (nije) dosta’ examines media literacy, journalism ethics, and the representation of marginalised groups in media. It offers actionable recommendations for combating fake news and proposes making media literacy a mandatory subject in the Croatian education system.

About the project

Supported by:

European Solidarity Corps

EU Youth Programme Priority:

Participation in Democratic Life

Topic:

Youth Participation / Promoting Participation for All

Visibility:

The project was featured on the Croatian Debate Society’s website and in Croatian news articles. An event brought together over 80 participants and their peers to present the works created during the project. The research paper ‘Pametnom (nije) dosta’ was shared with educators and stakeholders and made publicly available online for broader dissemination and impact.

Organisations involved: